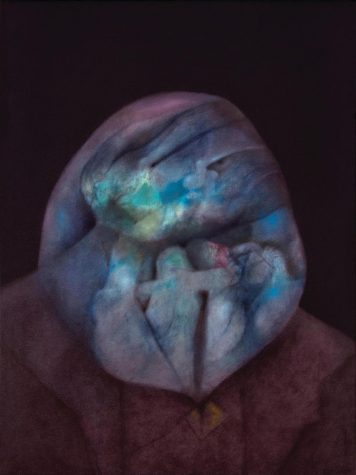

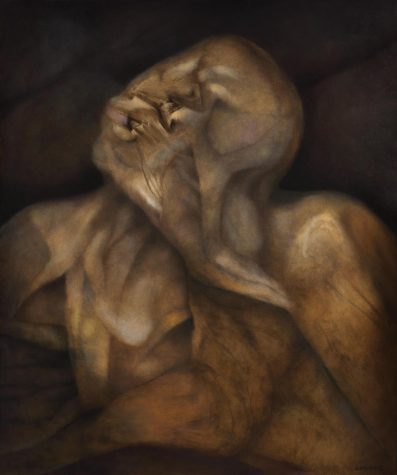

Documentary Puts Rafael Soriano’s ‘Cabezas’ Exhibition Into Perspective

April 23, 2019

The William Paterson University Gallery brushed a new stroke of perspective into Cuban artist Rafael Soriano’s paintings of heads Wednesday Apr. 10 by screening “La Profundidad del Silencio,” a documentary about Soriano’s life, in Ben Shahn Center for the Visual Arts.

The event is the latest in a series accompanying the traveling exhibit Rafael Soriano: Cabezas (Heads), co-curated by Kristen Evangelista, director of the University Galleries, and Dr. Alejandro Anreus. It is the first traveling exhibition organized at William Paterson, and the first time all of Soriano’s portraits of heads are being shown together.

Director Jorge Moya, who gave an introduction to the film before the screening, called it more of a “filmed conversation” than a documentary.

“I was hoping that young people in academia that didn’t have access to Soriano would discover his work, that it would help awaken an interest in his work and give them a certain amount of information that they wouldn’t have otherwise,” he said.

Rafael Soriano, who was born in 1920, is one of the most renowned Latin American artists of his generation. His early work reflected a geometric and surrealist style, but has been revered by more people in the art community for what he painted following his exile to Miami, Florida in 1962.

These particular works focus on the spiritual and metaphysical world.

“He was a scholar. He was very much in the world of academia. He helped found the School of Art in Havana,” Moya said. “I think his experience of exile, in that sense of uprootedness and looking for a place in his head to deal with all of it, is what took him to the dimension of mysticism and poetry and visual language that is really unique.”

The film features interviews with Soriano, his wife Milagros and poet and historian Ricardo Pau-Llosa. It pieces their words together with clips from the artist’s life and his paintings, set against music Soriano would listen to as he painted.

“This could have been a three-day documentary if I didn’t run out of film because Milagros could speak forever,” Moya said. “She was as much into his art as he was. She felt that she was blessed by living the experience of Soriano’s painting.”

The audience included students, Dr. Anreus, other faculty members and art enthusiasts, University Galleries manager Emily Johnsen, and Rafael Soriano’s daughter, Hortensia.

Hortensia Soriano, who flew to New Jersey from Miami to see the exhibit, said that the documentary, like her father’s paintings, shows her parents’ love story.

“I feel very proud and I feel a lot of love, because it’s not only my father, it’s my mother in those paintings, too,” she said. “She made those frames, she mounted his canvases. I look at those paintings, and I feel their love story, and I’m a product of that love.”

Asked to recall a special moment between her and her father, Hortensia described seeing her father’s finished paintings. Her father never discussed a painting until he finished it, so when he called Hortensia and Milagros to the back room of their home, Hortensia knew the painting was complete. Her father would then ask what they saw and felt, and the family would discuss it.

“Then they would proceed to name the painting. Much like one would name a child, they would name each painting,” Hortensia said. “It makes me feel like I’m a part of those paintings, too. They feel like my siblings.”

Hortensia described her father as a “master zen,” full of peace and tranquility.

“He was a man of few words, but when you paint like that, what more do you have to say?” Hortensia said. “What he needed to say, he would say it in his paintings.”

After the film screening, Dr. Anreus invited the audience to Ben Shahn Center’s South Gallery to view the exhibition.

“I found it very inspirational. Looking at the paintings, you can’t really see what they mean, but after watching the documentary, you kind of put two and two together,” said Ernestini Rojas, a junior and public health major at the gallery. “This is his way of interpreting his world and language.”

Dr. Anreus, who has written extensively about the heads, said the exhibit is a great opportunity for students to see art “of the highest order.”

“I think it opens up windows about transcendence, that life is more than just a material experience,” Anreus said. “These are pictures that speak about the mystery of existence, and the importance of surviving great trauma and loss, beginning again with an open heart and a great deal of courage. I think these paintings are ultimately about that, about spiritual courage.”

The exhibit was inspired by former university president Kathleen Waldron, who fell in love with Soriano’s work at the McMullen Museum at Boston College.

Waldron encouraged gallery director Kristen Evangelista to organize a showing of Soriano’s work at William Paterson, and Evangelista then approached Dr. Anreus about an exhibit.

Dr. Arenus said that the exhibition will resonate with students not only because of the important issues Soriano explored, but because of the artist’s background.

“He’s an immigrant and we’re a nation of immigrants, so it makes perfect sense,” Arenus said. “The other key thing is that William Paterson is almost a 34% Hispanic-serving institution, so I think it’s a perfectly fine thing to have exhibitions that will engage a particular student body.”

The exhibit opened Jan. 28 and will be on view until May 8. It will then travel to the Art Museum of the Americas in Washington D.C.

“I urge you to not only see the paintings, but visit them often until the closing date, because it’s not an opportunity that I think will be easy to experience again,” said Moya. “The more I see them, the more I appreciate them.”